What if you cut the store out of the retail experience?

I know, it doesn’t sound innovative. Online retailers have been doing this for years—saving money on the cost of renting retail space, of paying and training retail staff, and all of the other expenses that go with managing an on-site inventory.

Then again, online shopping isn’t much of an experience. But what if you could keep the experience and toss the store?

Enjoy is Ron Johnson's attempt to do just that—to reimagine the retail experience for the 21st century. You'll remember that Ron Johnson was the Target executive par-excellence who Steve Jobs recruited to create the Apple Store.

Johnson was always one to take on an impossible—or improbable—task. After graduating from Harvard Business School, he didn't take a job on Wall Street—he took a job stocking store shelves at the Mervyn's department store. Not because he needed to—but because he wanted to. Because he knew that to be a good executive, you needed to know how the business worked from the ground up.

At Target, he infused design and style into the retailer’s brand, transforming it from Tar- Get to Targé. When he left to join Apple, he was leaving for a company that had no stores, no iPhone, no iPad—and no real hope of competing against the likes of Best Buy and CompUSA.

While at Apple, Johnson turned the Apple Store from an idea into the most profitable retail store in history—a distinction that it still holds. Just before Steve Jobs passed away, Ron Johnson left Apple to assume the CEO post at JCPenney, returning to his department store roots. He was leaving the most successful store in history to board the sinking ship of a mall department store. And he didn't disappoint.

Within his first year, he had rethought the mall experience:

FAIR AND SQUARE

The first task: kill sales. Why? Because sales are a lie. Sales are sales in name only. A sale on what? A sale on the “suggested retail price.” Suggested by who? Items are routinely marked up to suggest that when stores "slash” them down, it’s a ‘sale.' Sales are a psychological game that retailers and shoppers play together. Consumers like it because they feel like they’re getting a deal. Sales help shoppers justify a purchase decision. And for the retailer, sales help to build loyalty. To control when and how inventory is sold. But it's all a game—an elaborate illusion. And both parties know it.

The problem? List prices keep inching higher and higher so that sales can seem ever more outrageous.

As Johnson explained at his 2012 launch event, a $10 item in 2002 was on average marked up to a $28 retail price. By 2011, customers could find a similar $10 item marked up as high as $40. From Johnson's 2012 JCP presentation.

This erodes trust, Johnson argued. Younger shoppers don’t want to play the game. They don’t have time to chase sales and cut coupons. Young shoppers just want to know that their store of choice is going to treat them fairly. To treat them with respect anytime they stop by. To treat them “fair and square.” Johnson’s plan was to kill sales to save the future.

YOUR FAVORITE STORE

Remember before smartphones, when the Internet wasn't in every pocket? Do you remember stopping by Apple stores just to check your email? I do. Even today, Apple Stores feel more like a technology playground than the pressure-cooker of a sales floor. It's fun—a place to try out technology with friendly experts. Johnson knows that place—Johnson designed that place. And he took that approach to JCPenney. The argument: because malls have in some ways replaced the Main Street, why not build a store that fulfills some of those community needs?

Johnson proposed a store where kids could get free haircuts before school. Where spouses could enjoy a cup of coffee while their loved ones shopped. Or friends could surf the Internet. Where anyone could just relax without being pressured to complete the sale. Johnson had a phrase: we're not interested in being the biggest store—or the flashiest store—we want it to be your favorite store.

STORES WITHIN STORES

Like any big department store, JCPenney sold many goods made by many different companies. Levi’s, Joe Fresh, Liz Claibourne. What if rather than haphazardly scrambling these products across a big empty space, you built specialty stores within your store? Levi’s would have its own special section designed with their aesthetic in mind—from floor to ceiling. Brands that couldn't afford a whole storefront in the mall could find a home in JCPenney. And customers could find a place to immerse themselves in the products and brands they cared about. Imagine if Levi’s wasn’t just a name on a display, but a place that you could visit?

It was a grand strategy. Aimed at updating the hundred-year-old brand of JCPenney—at attracting new customers, and truly building a unique retail environment. While at JCPenney, Johnson redesigned the look and logo, partnered with existing and new brands, mocked up an entire store in Texas, and started the big task of transition nationwide.

But the board of directors was restless. They wanted results yesterday. They couldn't wait for tomorrow.

In 2013, Ron Johnson stepped down after just a year and half on the job. For three years he's been quiet. Until today.

ENJOY

Enjoy is Ron Johnson's attempt to reimagine the retail store. It begins with no store:

To understand the ambition of this project, you have to first consider what a retail store is:

- A retail store gets products at a discount from the manufacturer.

- It sells these products for a higher price.

The difference between these two numbers is its revenue. This revenue is divided in two ways:

- EXPENSES: What it costs to buy the products and run the business.

- PROFITS: What you put in your pocket.

Now, for a retail store, those business expenses can include:

- Rental of the store

- Maintenance of the store (cleaning, painting, decorating, signage, etc.)

- Salesperson pay

- Salesperson training and development

- Technology (inventory management systems, pay terminals, etc.)

A store's expenses may also include things like:

- Warehousing (if necessary)

- A website (online ordering)

- Marketing

But let's pay attention to the five at the top. In an online store, what's different? Online stores cut out or significantly decrease the costs of those five items:

- Rental of the store

- Maintenance of the store (cleaning, painting, decorating, signage, etc.)

- Salesperson pay

- Salesperson training and development

- Technology (inventory management systems, pay terminals, etc.)

Online stores still may have other expenses, but by cutting out some key elements they can put the savings towards:

- INCREASED PROFITS: Now, an online store might like to increase profits—but online stores have an uphill battle against physical stores. It’s not easy to compete with the on-site convenience and expertise. So you can’t just pocket all of the savings. You have to put them to good use.

- DECREASED SELLING PRICE: This is the no-brainer choice. Pass a lot of the savings on to the consumer. This is what many online retailers do. Without as many expenses, they can undercut the prices of physical retailers.

- INVESTMENT THAT IMPROVES THE BUYING EXPERIENCE: This is another solid choice. Consider Amazon—which has invested tons of money in things that physical stores don't have to worry about, like shipping. An online retailer might also invest in better photographs, innovative apps, or—in the case of a store like Warby Parker—the cost of shipping sample products to try-on.

So, let's return to Ron Johnson's Enjoy. What is Johnson doing with the money saved from running physical stores? In which dimension is he investing?

- INCREASED PROFITS: Maybe.

- DECREASED SELLING PRICE: Nope. He is selling tech products for the same price as the MSRP.

- INVESTMENT THAT IMPROVES THE BUYING EXPERIENCE: Yes. But how?

Two dimensions:

- Fast delivery

- On-site training and set-up

This is a very interesting concept. Imagine if your average retail store in the mall closed shop, but kept the employees on payroll. Rather than serving as salespeople, you trained these employees as experts in the product. And asked them to deliver only items that were already sold.

Think about how this turns the buying process on its head. It assumes that the buyer know what needs to be known to make a purchase decision. And that employees are there to help after a purchase—rather than before.

This is a powerful assumption. It assumes that the buyer knows enough to decide, but not enough to fully enjoy their products. It is an assumption that perhaps wasn't possible before the Internet—when people could do their own research on a product.

The store, then, isn't a showroom for products—a place to try things out or try things on. It's a place to help you make the most of your purchases.

The relationship with the store doesn't end when you buy something—that's where the relationship truly begins. Where loyalty starts.

It's worth considering for a moment—is this assumption correct? Ask yourself: when is information and hands-on expertise most valuable to you? Before you make your purchase decision, or after?

Both are important—and both come in a variety of flavors:

BEFORE A PURCHASE:

- User reviews

- Spec sheets and advertisements

- Salesperson knowledge

- Expert guidance

- Hands-on experience and trials

AFTER A PURCHASE:

- Manufacturer guides

- User videos and tips

- Exploration and the user interface

- Expert guidance

Rather than asking which kind of information is more important, we should ask: which one is a store best equipped to help you with? Salespeople could help you before a purchase—but can you really trust a salesperson to have your best interest in mind? Before a purchase, spec sheets and advertisements, as well as user reviews, are probably better information sources. The best source before a purchase would be yourself, of course—if you could get actual hands-on experience and a free trial. Physical stores allow this to some degree.

For the after-purchase experience, information comes in a variety of forms. The primary source is the product itself—as you explore and use it. This brings up a meaningful question: is technology good enough to serve as its own guide?

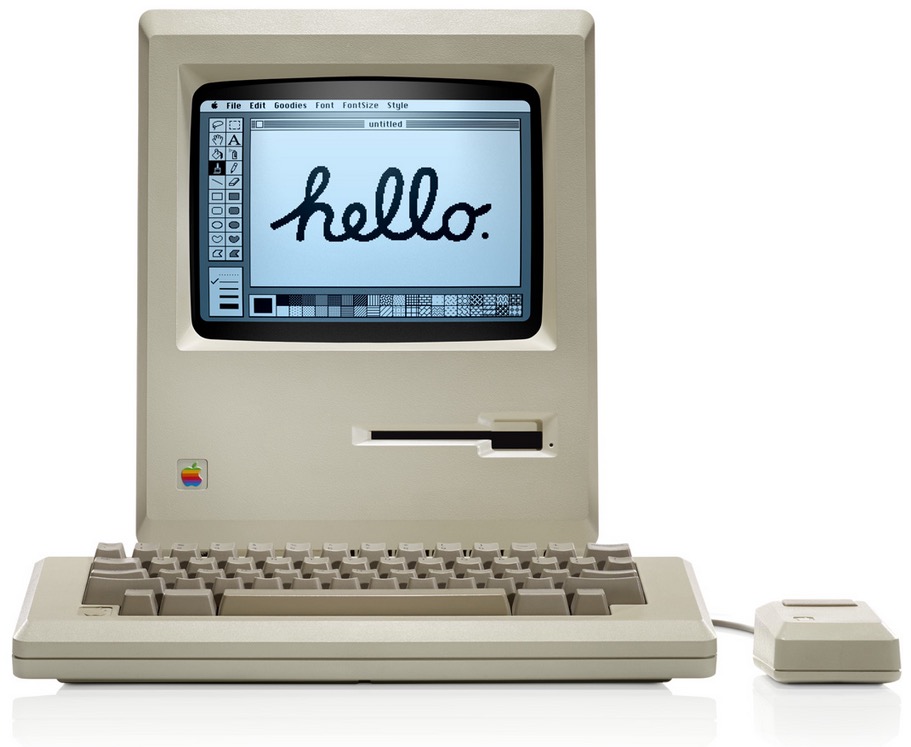

When Steve Jobs designed the first Mac, he envisioned a computer that was so easy to use, you didn't need a manual. It would be obvious. The interface of the first iPhone was designed with this in mind. Today, children and the elderly—two populations with limited technology experience—embrace the iPhone and iPad with glee. To a large degree, Apple was successful.

But as much as we might wish our technology was easy to learn—it also has to be useful. Ideally, technology should be easier to use than it is to learn. What do I mean by that?

We live in a world of technologies that require complex interaction. We are willing to put up with a learning curve if a product is useful enough. Take cars for example. Put a child in front of a car and they won't know enough to safely operate it. A car isn't its own user's guide. But over time, after training and study, it can be easy to operate. The same goes for learning how to operate diving equipment. Or to edit a video with professional software. No matter how easy our technology is to use day-to-day—there will always be a place for help on day one.

What value can Enjoy provide on day one?

Right now, Enjoy is only selling technology products. And technology is the perfect example of a complex product.

Just bought a new smart TV? It doesn’t matter if it only has two plugs. First you have to enter your wifi password, then your Netflix password. Then your iTunes password. Then your VUDU password. Then your YouTube login.

Just bought an Apple Watch? First you have to pair it with your iPhone. Is your Bluetooth on? Do you have enough power? Now you need to answer a few setting questions. Now you have to wait for it to sync.

It’s like your birthday as a little kid. You get exactly what you want—but batteries aren't included. Enjoy is like having the batteries included with every purchase.

EXPERT BATTERIES

How expert are these experts going to be? Ron Johnson said in a recent CNBC interview that you can expect delivery on the same day that you order—in just four hours. Think about everything that must happen in that four hours:

- The order goes through

- The item is retrieved from a warehouse or stockroom or personal garage

- The employee maps a route to the preferred meeting location

- The employee battles traffic to get there on time

Ron Johnson said that he doesn't believe in giving people "windows" of time—between 1 pm and 5 pm. No. If the meeting time is 3 pm—the knock on your door will come at 2:59 pm.

In that short four hours, is the employee also reading the user manual? Studying up on setup issues, features, tips and tricks? Expertise is critical to success. Are these employees really expert enough to fill one hour with expertise?

How does Enjoy ensure that its employees are up to date on the latest products? It will be very interesting to see how Enjoy develops its internal education and training. The company is effectively “teaching the teacher.” Is every employee expected to be an expert on every product—or will they have specialties? Geographically, it makes sense if any employee could answer any call—but these employees aren’t just drivers; they’re not even salespeople. They’re something entirely different: product experts.

Here’s another interesting question: Johnson is training retail employees as delivery drivers. But what if a delivery company like UPS or FedEx decided to train its drivers as retail employees? It would be fascinating if Enjoy’s major competitors came not from the retail space, but the delivery space. This could very well be the case—if people end up valuing immediate delivery more than day-one setup. Since the concept is so new, how many customers will take their delivery and simply say: ‘no thanks’ to set up?

SCALING ACROSS SPACE

Today, Enjoy launches in two cities: San Francisco and New York. That might sound strange for an online retailer—but Enjoy is more like a physical store: new locations require new infrastructure. Employees must be hired, trained, and coordinated. Inventory must be ordered, stored, and distributed. And the word must go out through local advertisements and press reports. Which leads to the question: how fast will Enjoy scale? Probably faster than the average retailer—because the average retailer needs to find a great location. To Enjoy, the whole city is the location. Which cities will be next?

SCALING ACROSS INDUSTRIES

Ron Johnson himself has said that this is just the beginning. Tech products today—tomorrow: the world. But how big is that world of products? Well, there are two value propositions to Enjoy:

- Immediate delivery

- Expert help on day one

So any product that can be immediately delivered fits the bill. And any product that you might need help with on day one. There are plenty of products that fit in one bucket but not the other:

Books would be great for immediate delivery. But you don’t need help setting them up. Large household items like fridges and washing machines would be great for expert setup—but these don’t fit into a car as easily as a pair of Bose headphones. Then again—Enjoy already says that you can pay $100 for an hour of expert help, even if you don’t buy the product from them. Therefore, it is conceivable that they could scale to offer expert help on products that they don’t sell or deliver directly.

The real excitement surrounding Enjoy, though, isn’t in the products—it’s in the expertise. Imagine Enjoy’s experts there for you with other purchases:

GROCERIES

You order groceries on a Sunday and four hours later there’s a knock at the door. Here are all of your groceries, and here’s an expert who can show you how to cook something extraordinary in 60 minutes or less.

CLOTHING

You order a new dress and four hours later, there’s a knock at the door. Here is your new dress and an expert stylist who can help you pick the right accessories to go with it—and warn you not to wash it with your other colored laundry.

HOME IMPROVEMENT

You order a kit for putting shelves up and four hours later, there’s a knock at the door. Here is your shelving kit and an expert who can help you figure out where to drill the holes in the wall, how to make sure they are level, and remind you of some common safety tips.

If the experts are expert enough, the possibilities are endless. Enjoy has to figure out how to make each product and delivery work for them cost-wise, but once they do, the sky’s the limit. Because as soon as customers understand the value of having an expert at home, on day-one—anything less will seem barbaric.

The success of JC Penney was held back by traditional thinking. Enjoy will be propelled forwards not by thinking—but by a feeling. An unlikely feeling in today’s retail experience: joy.

This isn’t disruptive technology, it’s disruptive emotion. And Ron Johnson has picked the right one.